Ever since watching a programme about it last Friday, I can't stop thinking about Gianlorenzo Bernini and his sculpture

The Ecstasy Of St Theresa. I feel haunted. In the most transient moments - sipping a cup of tea, throwing a bag over my shoulder to go out the door, turning over in my bed in the early morning, slicing potatoes on my plate, I see the image of St Theresa's enraptured face, turned upwards, her mouth open, the fine point of an arrow entering her, a spray of golden light behind, her robe in swathes around her like liquid sunshine.

It is almost a cliche now to talk of the greatest art as being created by the most messed up people. And true, there is much powerful art that is, and has, been created by men and women where neither mental illness nor egomania is the driving force. But equally as true, genius springs from what is incomplete, flawed, sordid, neurotic, stupid, disparate and ugly. From the gutters of despair, in the midst of crashing disillusion, loss, sorrow, hatred and violence (I wonder if life itself is only as beautiful as its own despair, only as pure as its worst filth, only as strong as the weakest, most despised runt of the litter).

I think of this when I look at the Ecstasy Of St Theresa, and when I remember Bernini's torrid life story, and his dramatic depiction of this woman, a holy woman, and, in particular, of her physicality, her face and body as the meeting place or conduit for divine revelation and bliss.

I think a woman's body, in

all its variations, is to me one of the most beautiful forms there is on this planet. It is one which has been, and still is the site of devotion, adoration, violation, reverence, contempt and horror in our world. Exalted, degraded, ridiculed, feared, controlled, desired in a million different ways, a woman's body is as complex as life itself, as death, as dying, as growth and decay, as desire, wanting and repugnance.

Sitting here now, under my clothes, I can feel the skin of this body that I breathe through, I can sense the blood circulating my veins, hear my heart beating in my ear if I press it to my shoulder. My breasts, my hips and vagina, my neck, legs, skin, hair, eyes, buttocks, feet, my back are all realities in and of themselves, but they're also the vehicle for a thousand different projections, some dazzling, some shimmering, some comforting, some lit up in the crudest red light or beset by howling laughter.

Some of these have been handed down to me through time, some are of my era, some through art, through philosophy, religion, culture, literature. Some are inside my own head, most surround me from the outside, from the voices of men, from the voices of women talking to men, from the voices of women who do not care what men have to say. From my mother, from my father.

Am I ever my own woman, I ask myself, can I ever escape this hall of mirrors, know my body beyond its own symbols?

I think of it split and ripped by giving birth, a cell multiplying inside it, growing into foetus, forming, enlarging, holding the blueprint for its own destiny, forming hands and feet, a nose, a throat. A life being born - my body as toil, violent music playing through a crackling stereo. A child moving through me, pushed out by labour and agony through the birth canal, ripped from my flesh, out into cold open air. The uncut umbilical cord, the bloody placenta.

Inside and through this female body, life is formed and grown and expelled with massive effort and incredible physical, mental and emotional intensity. And this intensity, this force and power is there, whether realised or not, in every single woman as part of her physical being.

To me, this force inside a woman is beautiful, and messy. It is complex and it is also the simplest force in the world. A force not different from that of the uncovered grave, a corpse peeping out at us from under the soil. Or from a puja on the Ganges, in a blazing light of candles. Or the baby floating past, its head, a bloated shrine. Its skin, grey.

And yes,

it is The Ecstasy Of St Theresa, hovering in the air. But it is also Bernini, the artist who carved it, a year before its conception, sunk to the floor, a nobody, a nothing, the memory of the failure of his greatest architectural ambition ringing in his ears.

As it is the epilieptic nun, scissoring in divine rapture across the wooden floor, eyes rolling in the back of her head. She is not pretty. She is not even beautiful. Only a coarse woollen robe, two pairs of old hands holding her spindled tattered frame in the sunlight that pours through the stained convent windows, too bright to bear without her palm across her face.

And this same force is also Bernini's illicit lover, Constanza, in marble, the loop of her cotton blouse pulled slightly undone, her eyes like wildfire in a forest at night, or a tiger esaped from the zoo, once leashed and captive, now, more than untamed: out of control, hunting, hunting down.

And it is Bernini's servant with a sword, slashing at Constanza's face in retribution until it is ribbons, the pillow soaked in her blood, the colour of her most beautiful dress, of her lust. She will never again have a face that can be immortalised in sculpture. The Muse becomes damaged goods, fallen from ecstatic grace, imprisoned for fornication, disfigured.

So it is Constanza who pays the greatest price for passion, and after nearly killing his own brother and scarring her face for life, the real perpetrator goes free: Bernini, the great hero of Rome becomes an even greater hero, the great hypocrite, scoundrel, egomaniacal amour, liar, destroys and violates in the name of love all that he once created and revered as beautiful, as divine. This woman who was his Muse, who became marble, who fired one of the greatest sculptors in history's world with a blaze of signifiers. Who torched it all with her own betrayal. Whom he will never want again. Whom he will never again watch sleeping through the night, holding his breath lightly so as not to wake her. Whom he will never long to press her small head into his chest as though she were his own restless child.

And now her face is a map of stars, all traced in blood, her honour a withered flower, her wildfire burnt out beyond all reason. Where is left for the woman to go? At Bernini's command she is again caged, this time in a damp prison cell without light, in rags and humiliation, taught the lesson that all women who play with fire must learn in 17th century civilisation, the image of her passion, her beauty, her womanhood, consigned to a sunless locked vault.

This same man conceived and gave birth to the remarkable, transcendent

Ecstasy Of St Theresa, long after the light had left his eye, long after such tragedy and violence, after his own sudden descent into failure and his turning to God. And this same woman, Constanza, also gave birth to it, and is enfolded within the creases of St Theresa's robes, in the openness of her mouth, her half closed eyes, though almost certainly neither she or Bernini will have ever known, will ever know this.

Woman, Muse, sister, daughter, mother, virgin, slut, truth, beauty, warfare, corruption, fertility, deceit, the earth, the stars, the moon, the fields, the tether, the breaking of all mundane bonds, the higher, the lower, animal, angel, divinity, a flower, a rose, the scent of death...these words and images haunt me, as the Ecstasy Of St Theresa haunts me, as Constanza and the nun haunt me, as a woman who, like every other woman, is

all of these things, who is Constanza and St Theresa, Bernini and the ecstasy itself, and, who, in the middle of the night, or when sipping tea, or throwing a bag over her shoulder to go out of the door, slicing potatoes, is none of them, never has been, and never will.

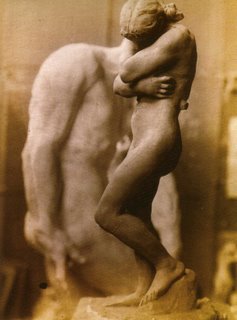

(top image: 'Eve', Rodin's studio, 'Cain' in background.)

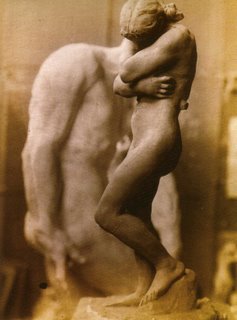

(top image: 'Eve', Rodin's studio, 'Cain' in background.)