A couple of Saturdays ago, I went with a friend to Catholic Mass at a local Brighton church. The yearning to go there had started before Christmas, when feelings of grief over my Mum's condition peaked, and I couldn't see any real point in existence, if where it was to lead ultimately was simply dissolution, pain and death. The need for something big enough to hold this experience came to a crisis point.

What actually moved things on for me was listening to a talk by a Buddhist Order Member, Danavira, on death and dying. I sat, lights out, in my front room for two hours listening to the recording. The impact of it went directly into my veins and bones. It took on the horror, the devastation, the messiness and complexity of death, and ultimately, its utter profundity. Danavira's words were big enough to meet the immensity of my insights and emotions over what it means to live and to die, to be born and to decay.

Months earlier, in October, I walked up Snowdon with Bob, the first time I have ever hiked up a significantly large mountain. I found, in the climbing, that, having seen my Mum in hospital just days before, this was a mountain huge enough and powerful enough to take my grief, big enough even to hold Mum herself in her dying state. So tiny, I was, climbing the vast expanse of its stomach, I knew that the mountain understood and held me fast. Now, I am not speaking symbolically or poetically here when I speak of the mountain holding me, I mean it absolutely literally. I tangibly felt that presence and character of the mountain surrounding me. Because of that, all my grief and sorrow turned to amazement. That one primal, unanswerable question that I ask myself in every moment of grieving, "How come?" returned to me in the single voice of the mountain, not through words, but through a sound. It was a resonating hum, that the peaks and the valleys and the woodlands and birds and the small climbing bodies of hikers were all making. This is it. This is my answer. Everything I need is here.

I was surprised, then, when it was talking about Saints and Catholic Mass with some Catholic friends of mine that aroused such a strong feeling of yearning in me, rather than Buddhism. After over eight years of Buddhism being almost my whole world, in terms of way of life, friends, commitment and philosophy, I have drifted from it over the last few years, in order, I think, to go more deeply into my own experience of how things are and who I am, through writing, poetry and making music. Language, specifically poetry, and music, unlock realms of reality and experience I've never known before, and I can only seem to experience them through creating in this way.

And when I had what might be called mystical experiences some years ago, which totally tore down and rearranged my life, it wasn't Buddhist teaching that I felt was being revealed to me directly, but a direct and non-rational experience of healing, grace, and the presence of angels. This disturbed me greatly at the time, as it didn't fit with what I believed of reality, and not many people around me seemed to know what I was on about; only the the reiki healers, the lost shamans, the acid casualties, the people who had found God on the roadside.

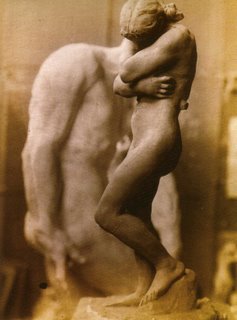

I have always been attracted to the imagery of Christianity, to the blood and redemption, the wounds of Christ, the choirs of angels and the Saintly lineage. But there is more to it than that. I am drawn to the lineage of Christian mystics in the same way that I am drawn to the lineage of Nyingma cave-dwellers, or the seekers of Divine union in Sufism. The practice of direct communion with God, if you call it that, or with Reality or The Divine, if you call it that instead, feels like the truest form of practising any religion for me personally. It is helpful at times for someone to tell me about God or The Buddha or the holiness of existence, but ultimately, I have to plug into that directly myself. And that is never easy. But I relate to the convulsions and stripped back wonder of certain Saints, the fighting of demons in the mountains, the visions, revelations, hallucinations, the manifestation of stigmata, the terrible angels of beauty descending. And I relate because it feels like a world that I already live in.

Going to Mass that day blew my mind. The ritual blew my mind. No wonder the Spanish go to the bullfight on the Saturday and then take Communion on Sunday. The two seem inextricably entwined, to me, bullfighting and Catholicism. And the Mass spoke to parts of me that even Buddhism has not reached. It is poetry to me, amazing, cataclysmic poetry. And, if I look at it it as anything but poetry, in the biggest sense of the word, my fear is that it is also quite possibly a form of madness. In this way, I am still scared of Catholicism, rightly or wrongly, in, as one overseas friend described it, its strange rites of supernatural cannibalism. But then I have always been attracted to things that dwell in equal shares of darkness and light, and poetry did always tread those pathways between the sane and the crazily lost.

I was scared at the thought of returning to the Convent. I was scared that I would be disappointed by what I found there. I was scared that I would not be disappointed and that it would show me all I hoped for and suspected was there.

When I rang the Convent bell, an old nun came to the door and invited me in. I said to her "I used to live in the house next door, for over twenty years. But we moved out years ago." I had no idea if she was even at the Convent during that period, as I know that most of the nuns from then have either moved on or died. She smiled at me and said " Are you Clare?"