When I was in Darjeeling eight years ago, I stayed with a woman of 60 years or so who went by the name of Mrs Ongel. She had a penchant for poker and Padmasambhava, with dark eyes that curled up at the edges when she was concentrating on winning a game, and that danced with laughter when she played with her young granddaughter, Tara.

One evening, as my boyfriend and I wound our way through the narrow streets of Darjeeling back to Mrs Ongel's, we came across a strange woman with jet black dishevelled hair and a rather crazed look in her eye who was sweeping the cobbled street with a fervour I had never before seen devoted to such a job.

The next morning at Mrs Ongel's, as she shuffled her cards and offered us tea, we mentioned the woman, commenting on how unusual it was to see a woman doing such a traditionally male job, (it seemed rare for that to happen in Nepal at that time), and so late into the evening. Mrs Ongel just smiled and said "Ah, that is Pogli. That is not how she makes her living, that is just what she does, you know, for the sake of it. Because she is, well, pogli."

I mulled this over.

"Pogli?" I re-iterated.

"Yes," smiled Mrs Ongel, "We call her Pogli because that is what she is, you know, p..o..g..l..i..". As she mouthed the word slowly, she started making hand gestures, pointing her forefinger at the side of her head and circling it rapidly. In the end, we got it: Pogli was someone who, in Mrs Ongel's mind was off the rails, a bit crazy, 'got a screw loose'. Her hands flapped in the air.

I never forgot this, nor did I forget my time at Mrs Ongel's, with her gambling ways and her serious devotion to Tantric practice. For the rest of the trip, and upon my return to England, indeed for all the subsequent time since then, the word pogli, or poglie, as I sometimes spell it (for I have no real idea of how it is spelt or even if Mrs Ongel's explanation of the term or indeed my interpretation of her description was correct), has become a significant word in my own personal dictionary, a mainstay of my communication, somehow filtering into my language and descriptions.

And so I have, for my own purposes, adapted this word to describe a state of being that I have never before had words for, and desperately wanted a term to describe: that is, something or somebody: it could be a moment, a behaviour or an action, it could be a way of thinking, it could be a place, or even an object, that is inherently, indefatigably, eccentric, odd, unusual, silly, strange or not able to fit into conventional society or experience. And, to put my slant on it further, that, in its eccentricity, is undeniably charming, endearing and life-affirming. To me, that is pogli. And so I have incorporated and re-framed this word, frankly, because I see and experience so much in this world and life that is frankly, pogli beyond belief, and that otherwise,I have no language for.

In fact, in my own purloining of this word, I would not only put the black haired obsessive compulsive street sweeper of Darjeeling into this bracket, but also Mrs Ongel (her name can be translated as Mrs Angel for heaven's sake), and no doubt myself at the time, working my way, as I was, through some of the holiest places on the planet, attempting to track down the elusive Dzogchen master Chatral Sangye Dorje, sitting in caves waiting for an emanation of Guru Rinpoche to appear, attempting to practise shooting my consciousness out through the top of my head with about 500 other Tibetan monks and lay people on retreat, throwing up on a regular basis and reading too much William Blake. In fact, I would go as far as to say, that, though all countries undoubtedly have their aspects of pogliness, if pogli is a throne at which the powers of the strange and wonderful and occasionally bananas sit, India must surely be its queen.

So there we have it, the power of the pogli.

So I explain this so as to be able to say to you: yesterday was a pogli day. I first realised it was going to be pogli when I woke up in the morning and remembered my dream. In it, I was living alone in a tumble down version of my old family home, the only other memorable item in my house being an old and bent metal framed pair of spectacles which belonged to Karl Marx. They hung inconspicously and somewhat sadly on my lounge wall. And somewhere, in a distant room, the ghostly image of Marx's grandson floated above the carpet, himself now sixty, with a large belly and paunchy face, having convulsions, as he sweated and and struggled to breathe on a white table. Outside the house, reporters gathered, and I discovered through reading a newspaper that years ago my father had bought a Faberge egg which was now worth 30 million pounds, and it was still somewhere in the house. But I couldn't be bothered to look for it.

So when I drove up the Upper Lewes Road, that morning, and spotted not just one, but four identical pairs of black converse boots suspended mid air from their laces from the middle of the telephone wire, 50 foot above the road, I was starting to feel that the power of the pogli might be with me that day.

We then stopped off at Sainsbury's, for my companion to buy a box of Celyon tea and several packets of hobnob biscuits (the ones with vanilla and chocolate cream in the centre), to which he seems to be firmly addicted (he keeps them in a rather impressive biscuit barrel, and when I noticed he had attached with sellotape a paper sign on the lid asking: what is it you really want?, I asked him if this worked as a deterrent, he replied, " No, I just realised that what I really wanted was biscuits"). Approaching the supermarket, I then noticed that the Welcome sign on the side of the building had been altered by somebody, and now read: hell: we bury ewe.

This significantly cheered me up, as it was, early on a Saturday morning, and I still felt like I should be tucked up in bed dreaming, whether it was of Marx's spectacles or not. I then sat in the car and listened, whilst my companion searched for hobnobs, to a radio programme about the National Lying Festival, held in Cumbria, in which men and women compete for the title of the best fibber in the land. Apparently it all began out of the tales that locals would regale visitors to their region with, and, who, usually upper class, with a naive and patronising view of the 'backward' yokels, would believe every ridiculous story spun them. And so, to poke more fun at their guests, the locals' tales got more and more silly and improbable, as the visitors would shift uncomfortably in their pub seats over an ale, trying to work out, puzzled looks on their faces, who the real stupid one sitting at the table was.

We then drove through the rain to my companion's house to take it in turns to stand for the rest of the day on a wobbly plank that we slid into one large ladder and one small ladder at each end, twenty foot in the air, in an attempt to paint his stairwell three different shades of cream, whilst he took regular flights towards the kitchen to make another cup of tea, and towards the living room to grab his banjo and, break, spontaneously and wonderfully into exhuberant twangs and twiddles of fine banjo music.

Upon returning to my flat on the evening, I was visited by the Bob, and, well, frankly, that requires no explanation as to how or why that might have been somewhat pogli, given that Bob just is pogliness personified, at least in moments that come with delightful frequency (he recently invented a blog called the that bloke's bike's back brake block's broke blog).

I mean, really, the whole world is pogli, we all know that: it just pretends it isn't. And this is a world I want to live in, a world where people hang shoes from telephone wires, and hold Lying Competitions and play the banjo when they are supposed to be doing up their house. Where there is room for women who sweep the streets for its own sake, and, though they might get a little teased for it, are accepted as part of society, and regarded with affection. Where people devote serious time and energy to cataloguing the minutiae of birdsong, and a girl with wonky specs writes for far longer than her arms are happy with, about stuff and nonsense, lost in memories of India and Nepal, and fleeting angels, lost gurus, and tumbledown buildings where men in smocks blow horns making ridiculous sounds, and mantras of devotion are chanted over and over and over again to the spirit of some ragged and beautiful, absurd truth.

Sunday, November 26, 2006

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

Catch-Up

I spent yesterday afternoon in bed with a hot water bottle and my toy dog, nursing a sore and menstrual belly. I took this time to slip in and out of the waking world to the sound of Joanna Newsom's new album Ys, her follow up to The Milk Eyed Mender .

To me, Joanna Newsom's songs transcend time and space, slipping between this world and all those others which spin together in this incredible and mysterious universe we call ours. And her voice is amazing, somehow sounding both direct and a thousand places at the same time, ageing and ageless. At some points she sounds no more than five years old, at others, she is a mature woman with lines creeping upon her face. Sometimes I can hear her at eighty five, others, she is a voice beyond all time, rattling down the centuries. She weaves her melodies through the cracks of existence and takes us with her down deep into the grass with the insects and the dew, humming across the sea bed to the tops of shipwrecks, spinning dark energy from her fingers, hanging from the corners of stars as she shouts entire verses about meteors and wheelbarrows and I am flabbergasted, left with huge tears in my eyes.

I love it when song can do this to me, when I am a balloon filling with vowels and consonants, crescendos and cadences. When it takes me to those worlds I always longed to go to, or that have become some distant memory, buried deep in the back wall of my being, or even that I never knew existed. When I listen to albums such as Ys, I know it can hold me, in anything, in the same way that a mountain or a wide green open field can, and that reminds me of the immense power that potentially lies in music and in words.

I felt similarly when I watched David Attenborough's Planet Earth last Sunday night on television. This is an extraordinary series, I never fail to be dazzled by the cinematography of this programme, as it tracks the natural world in all it's beauty and complexities. On Sunday, it was about jungles, from the tops of the tallest trees to a man who sat 300 hours alone in a hide in order to catch just a few shots of three birds of paradise performing their mating dances. From colugos, strange squirrel-like creatures that glide through the air from tree to tree by flaps of skin which attach, bat-like, from their bodies to their furry arms, to raiding chimpanzees, capturing and killing a rival member of a tribe, passing its bodily parts and head around to be eaten. It travels from the most impressive, beatific sights in nature to the most horrific, from the vastest to the tiniest all over the world. At one point it filmed a clearing in a jungle over the period of one year, but speeding the film up to show it all in a few minutes. It was clear from watching how these plant forms were growing and moving, how intelligent all forms of life are, as they travel and expand to the tune of their own logic and sense of instinctual survival. Seeds and pods burst to bud, to stalk and to vine, find their way across fallen trunks, scaling trees, climbing towards life and light. The plant kingdom is an entire universe in itself, governed by its own laws and logic.

For much of existence in the world, we humans are utterly insignificant save for the harm or good we inflict on them or their habitat. The animals go about life their way, the insects are indifferent to our desires or our dreams, plants and fish travel through their universes as we travel through ours. The toad belches and sings his way through the night, and it is his night, just as the child clutches his blanket and stares wide eyed and white faced at the shadows thrown by the cupboard door, and his world and the frog's world are as real as any I can muster. A flower knows how to court the bees and feed from the forest. The spider always knows the best way for a spider to be.

I wish I had a great mind for science and logic, I would love to study biology and geology, physics and maths. But my brain is as slow as a tortoise up Mount Everest at such things, stubbornly refusing facts and figures into its depths, preferring always the poetry and images that they conjure, the skew-wiff angle, the endless unravelling, the bits that escape definition, the non-rational, intuitive. Give me Derrida, I'll lap him up with a big spoon. Give me quantum physics and I'm there for five hundred years scratching my head to understand just three words, (despite the fact that I don't see a world of difference between quantum physics and deconstruction in the first place). So I'll refrain from saying something deep and meaningful in a factual way about the universe here now, despite feeling like this post needs it right now. Maybe I can leave that to the beloved Bob, who is currently residing in a tiny caravan alone in a wood somewhere in Sussex, probably eating RicePots and working out another law of the universe as I speak, and who blows my mind about such matters on a regular basis.

Well, it's been such a while since I last posted, so I might have known this would end up a long ramble. And I haven't even recounted all that has happened since I've been away. Suffice to say, I've been favouring music over writing for the last few weeks, hence my absence here, and it's been a productive time in that respect. I've recorded five of my songs for a demo with the help of the lovely Tom, who, aswell as being a dear friend, is also a wonderful songwriter and a talented musician. I've also been teaming up with others to collaborate and jam and things feel exciting for me musically at the moment.

Other things I've been up to recently: poetry submissions, being skint, sobbing daily at The Jeremy Kyle Show (move over Pete Doherty, he's my new hero), my acting debut as a grieving pale faced, black dressed sister who turns into a chiwauwa in Tony's new short and very weird (and good) film, previewed at the Duke of York's on Saturday. Eating lots of Turkish Delight and discovering the Choccywoccydoodah cafe (we're talking a piece of cake the size of your head, a cafe equivalent of an opium den), realising at 33 and a size 14, I'm never going to make it as a Supermodel, not cleaning my flat, loving, mourning, feeling romantic, occasionally reading and falling off my bicycle.

That should do for now.

To me, Joanna Newsom's songs transcend time and space, slipping between this world and all those others which spin together in this incredible and mysterious universe we call ours. And her voice is amazing, somehow sounding both direct and a thousand places at the same time, ageing and ageless. At some points she sounds no more than five years old, at others, she is a mature woman with lines creeping upon her face. Sometimes I can hear her at eighty five, others, she is a voice beyond all time, rattling down the centuries. She weaves her melodies through the cracks of existence and takes us with her down deep into the grass with the insects and the dew, humming across the sea bed to the tops of shipwrecks, spinning dark energy from her fingers, hanging from the corners of stars as she shouts entire verses about meteors and wheelbarrows and I am flabbergasted, left with huge tears in my eyes.

I love it when song can do this to me, when I am a balloon filling with vowels and consonants, crescendos and cadences. When it takes me to those worlds I always longed to go to, or that have become some distant memory, buried deep in the back wall of my being, or even that I never knew existed. When I listen to albums such as Ys, I know it can hold me, in anything, in the same way that a mountain or a wide green open field can, and that reminds me of the immense power that potentially lies in music and in words.

I felt similarly when I watched David Attenborough's Planet Earth last Sunday night on television. This is an extraordinary series, I never fail to be dazzled by the cinematography of this programme, as it tracks the natural world in all it's beauty and complexities. On Sunday, it was about jungles, from the tops of the tallest trees to a man who sat 300 hours alone in a hide in order to catch just a few shots of three birds of paradise performing their mating dances. From colugos, strange squirrel-like creatures that glide through the air from tree to tree by flaps of skin which attach, bat-like, from their bodies to their furry arms, to raiding chimpanzees, capturing and killing a rival member of a tribe, passing its bodily parts and head around to be eaten. It travels from the most impressive, beatific sights in nature to the most horrific, from the vastest to the tiniest all over the world. At one point it filmed a clearing in a jungle over the period of one year, but speeding the film up to show it all in a few minutes. It was clear from watching how these plant forms were growing and moving, how intelligent all forms of life are, as they travel and expand to the tune of their own logic and sense of instinctual survival. Seeds and pods burst to bud, to stalk and to vine, find their way across fallen trunks, scaling trees, climbing towards life and light. The plant kingdom is an entire universe in itself, governed by its own laws and logic.

For much of existence in the world, we humans are utterly insignificant save for the harm or good we inflict on them or their habitat. The animals go about life their way, the insects are indifferent to our desires or our dreams, plants and fish travel through their universes as we travel through ours. The toad belches and sings his way through the night, and it is his night, just as the child clutches his blanket and stares wide eyed and white faced at the shadows thrown by the cupboard door, and his world and the frog's world are as real as any I can muster. A flower knows how to court the bees and feed from the forest. The spider always knows the best way for a spider to be.

I wish I had a great mind for science and logic, I would love to study biology and geology, physics and maths. But my brain is as slow as a tortoise up Mount Everest at such things, stubbornly refusing facts and figures into its depths, preferring always the poetry and images that they conjure, the skew-wiff angle, the endless unravelling, the bits that escape definition, the non-rational, intuitive. Give me Derrida, I'll lap him up with a big spoon. Give me quantum physics and I'm there for five hundred years scratching my head to understand just three words, (despite the fact that I don't see a world of difference between quantum physics and deconstruction in the first place). So I'll refrain from saying something deep and meaningful in a factual way about the universe here now, despite feeling like this post needs it right now. Maybe I can leave that to the beloved Bob, who is currently residing in a tiny caravan alone in a wood somewhere in Sussex, probably eating RicePots and working out another law of the universe as I speak, and who blows my mind about such matters on a regular basis.

Well, it's been such a while since I last posted, so I might have known this would end up a long ramble. And I haven't even recounted all that has happened since I've been away. Suffice to say, I've been favouring music over writing for the last few weeks, hence my absence here, and it's been a productive time in that respect. I've recorded five of my songs for a demo with the help of the lovely Tom, who, aswell as being a dear friend, is also a wonderful songwriter and a talented musician. I've also been teaming up with others to collaborate and jam and things feel exciting for me musically at the moment.

Other things I've been up to recently: poetry submissions, being skint, sobbing daily at The Jeremy Kyle Show (move over Pete Doherty, he's my new hero), my acting debut as a grieving pale faced, black dressed sister who turns into a chiwauwa in Tony's new short and very weird (and good) film, previewed at the Duke of York's on Saturday. Eating lots of Turkish Delight and discovering the Choccywoccydoodah cafe (we're talking a piece of cake the size of your head, a cafe equivalent of an opium den), realising at 33 and a size 14, I'm never going to make it as a Supermodel, not cleaning my flat, loving, mourning, feeling romantic, occasionally reading and falling off my bicycle.

That should do for now.

Saturday, November 04, 2006

Constanza and The Nun

Ever since watching a programme about it last Friday, I can't stop thinking about Gianlorenzo Bernini and his sculpture The Ecstasy Of St Theresa. I feel haunted. In the most transient moments - sipping a cup of tea, throwing a bag over my shoulder to go out the door, turning over in my bed in the early morning, slicing potatoes on my plate, I see the image of St Theresa's enraptured face, turned upwards, her mouth open, the fine point of an arrow entering her, a spray of golden light behind, her robe in swathes around her like liquid sunshine.

It is almost a cliche now to talk of the greatest art as being created by the most messed up people. And true, there is much powerful art that is, and has, been created by men and women where neither mental illness nor egomania is the driving force. But equally as true, genius springs from what is incomplete, flawed, sordid, neurotic, stupid, disparate and ugly. From the gutters of despair, in the midst of crashing disillusion, loss, sorrow, hatred and violence (I wonder if life itself is only as beautiful as its own despair, only as pure as its worst filth, only as strong as the weakest, most despised runt of the litter).

I think of this when I look at the Ecstasy Of St Theresa, and when I remember Bernini's torrid life story, and his dramatic depiction of this woman, a holy woman, and, in particular, of her physicality, her face and body as the meeting place or conduit for divine revelation and bliss.

I think a woman's body, in all its variations, is to me one of the most beautiful forms there is on this planet. It is one which has been, and still is the site of devotion, adoration, violation, reverence, contempt and horror in our world. Exalted, degraded, ridiculed, feared, controlled, desired in a million different ways, a woman's body is as complex as life itself, as death, as dying, as growth and decay, as desire, wanting and repugnance.

Sitting here now, under my clothes, I can feel the skin of this body that I breathe through, I can sense the blood circulating my veins, hear my heart beating in my ear if I press it to my shoulder. My breasts, my hips and vagina, my neck, legs, skin, hair, eyes, buttocks, feet, my back are all realities in and of themselves, but they're also the vehicle for a thousand different projections, some dazzling, some shimmering, some comforting, some lit up in the crudest red light or beset by howling laughter.

Some of these have been handed down to me through time, some are of my era, some through art, through philosophy, religion, culture, literature. Some are inside my own head, most surround me from the outside, from the voices of men, from the voices of women talking to men, from the voices of women who do not care what men have to say. From my mother, from my father.

Am I ever my own woman, I ask myself, can I ever escape this hall of mirrors, know my body beyond its own symbols?

I think of it split and ripped by giving birth, a cell multiplying inside it, growing into foetus, forming, enlarging, holding the blueprint for its own destiny, forming hands and feet, a nose, a throat. A life being born - my body as toil, violent music playing through a crackling stereo. A child moving through me, pushed out by labour and agony through the birth canal, ripped from my flesh, out into cold open air. The uncut umbilical cord, the bloody placenta.

Inside and through this female body, life is formed and grown and expelled with massive effort and incredible physical, mental and emotional intensity. And this intensity, this force and power is there, whether realised or not, in every single woman as part of her physical being.

To me, this force inside a woman is beautiful, and messy. It is complex and it is also the simplest force in the world. A force not different from that of the uncovered grave, a corpse peeping out at us from under the soil. Or from a puja on the Ganges, in a blazing light of candles. Or the baby floating past, its head, a bloated shrine. Its skin, grey.

And yes, it is The Ecstasy Of St Theresa, hovering in the air. But it is also Bernini, the artist who carved it, a year before its conception, sunk to the floor, a nobody, a nothing, the memory of the failure of his greatest architectural ambition ringing in his ears.

As it is the epilieptic nun, scissoring in divine rapture across the wooden floor, eyes rolling in the back of her head. She is not pretty. She is not even beautiful. Only a coarse woollen robe, two pairs of old hands holding her spindled tattered frame in the sunlight that pours through the stained convent windows, too bright to bear without her palm across her face.

And this same force is also Bernini's illicit lover, Constanza, in marble, the loop of her cotton blouse pulled slightly undone, her eyes like wildfire in a forest at night, or a tiger esaped from the zoo, once leashed and captive, now, more than untamed: out of control, hunting, hunting down.

And it is Bernini's servant with a sword, slashing at Constanza's face in retribution until it is ribbons, the pillow soaked in her blood, the colour of her most beautiful dress, of her lust. She will never again have a face that can be immortalised in sculpture. The Muse becomes damaged goods, fallen from ecstatic grace, imprisoned for fornication, disfigured.

So it is Constanza who pays the greatest price for passion, and after nearly killing his own brother and scarring her face for life, the real perpetrator goes free: Bernini, the great hero of Rome becomes an even greater hero, the great hypocrite, scoundrel, egomaniacal amour, liar, destroys and violates in the name of love all that he once created and revered as beautiful, as divine. This woman who was his Muse, who became marble, who fired one of the greatest sculptors in history's world with a blaze of signifiers. Who torched it all with her own betrayal. Whom he will never want again. Whom he will never again watch sleeping through the night, holding his breath lightly so as not to wake her. Whom he will never long to press her small head into his chest as though she were his own restless child.

And now her face is a map of stars, all traced in blood, her honour a withered flower, her wildfire burnt out beyond all reason. Where is left for the woman to go? At Bernini's command she is again caged, this time in a damp prison cell without light, in rags and humiliation, taught the lesson that all women who play with fire must learn in 17th century civilisation, the image of her passion, her beauty, her womanhood, consigned to a sunless locked vault.

This same man conceived and gave birth to the remarkable, transcendent Ecstasy Of St Theresa, long after the light had left his eye, long after such tragedy and violence, after his own sudden descent into failure and his turning to God. And this same woman, Constanza, also gave birth to it, and is enfolded within the creases of St Theresa's robes, in the openness of her mouth, her half closed eyes, though almost certainly neither she or Bernini will have ever known, will ever know this.

Woman, Muse, sister, daughter, mother, virgin, slut, truth, beauty, warfare, corruption, fertility, deceit, the earth, the stars, the moon, the fields, the tether, the breaking of all mundane bonds, the higher, the lower, animal, angel, divinity, a flower, a rose, the scent of death...these words and images haunt me, as the Ecstasy Of St Theresa haunts me, as Constanza and the nun haunt me, as a woman who, like every other woman, is all of these things, who is Constanza and St Theresa, Bernini and the ecstasy itself, and, who, in the middle of the night, or when sipping tea, or throwing a bag over her shoulder to go out of the door, slicing potatoes, is none of them, never has been, and never will.

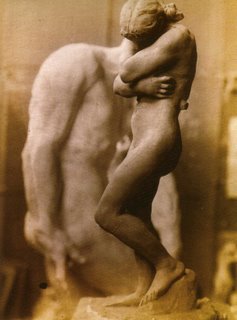

(top image: 'Eve', Rodin's studio, 'Cain' in background.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)